“I think I said, so what?”

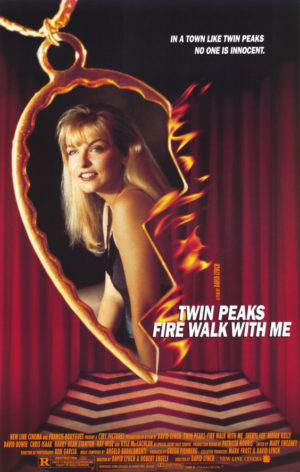

When director David Lynch’s film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me premiered at the Cannes Festival 25 years ago, it was met with much displeasure from fans of the original Twin Peaks television series. For most it revealed the wizard behind the curtain; it was a mystery with very little mystery. On the contrary, seeing this film in isolation brings the underlying context of the series into plain view and allows audiences to slip into the demonic, dejected dreamland or to tap out at the first sight of Bob creeping into her bedroom window.

Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee) seems to have reached the top of high school’s self-actualization pyramid; she is homecoming queen and has men at her beck and call. Her hometown is eerie and closed off and the adjourning townsfolk joke and laugh when the government agents show up to investigate the murder of a young woman named Teresa Banks (Paula Gidley). Palmer is convinced that no one knows her true self, she is addicted to cocaine, and it is revealed that she has been sexually abused for many years. This film is a concoction of confusion but a reboot-able watch in most of today’s cut and dry murder mysteries. I am convinced that if Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch were to be reincarnated, he would be David Lynch.

The sparse segments of incredulity snap the viewer out of the Twilight Zone – for lack of a better reference. One bothersome example: the (second) agent on the Banks’s case tells his deputy director he has a “feeling” the murderer will strike again. During an autopsy of Banks’s body, they found a small letter “T” under her fingernail – this single-handedly turns a crime of passion into a passion for crime.

Human suffering is in vogue even in 2017, which is why a story like Twin Peaks’ is still alive and kicking (with a Showtime reboot nonetheless). David Lynch’s focus on eyes and the use of rewinded audio only added to the confused expression that I held the entire film. A dichotomy between film and theater that I have always appreciated is the ability to see an actor’s expression within a centimeter of their faces. Lee’s desperation and suffering are evident in her piercing green eyes – eyes she shares with Palmer’s father, Leland (Ray Wise). The shots are fleeting yet meaningful, reminding me exactly of the “behind the scenes” viewpoint used in the films Get Out and by directors James Wan and Guillermo del Toro.

I am typically a fan of psychological horror but I need my “netherworlds,” for lack of a better term, to have simultaneous unpredictability and structure. Lynch has neither. However, this very reason is why audiences continue to be fascinated by the surreal (see Stranger Things which surely could not exist in a pre-Twin Peaks, pre-Lynchian world). During the search for clues, the two original agents investigating Banks’s murder search her trailer and speak to the trailer park manager. The character has a realism that I wish extended into other characters in the film. He was confused but seemingly honest, frustrated with the weird brand of tourism that has popped up around Banks’s murder; he just wants to enjoy a cup of “Good Morning, America.”

This film is absolutely mad. Lynch’s short spurts of unpredictability are akin to stepping on hot coals. For experts, the walk can last as long as they’d like, they’re used to the burning and may even enjoy it. For newcomers, it can be a Fire Walk through hell – but will it be to hell and back?

Part 17 Twin Peaks: The Return airs September 3rd.